The potentiometer is one of the most widely used electronic components found in all types of circuits. With its simple yet versatile three-terminal design, it provides adjustable analog voltage division for all manner of inputs and controls. While potentiometers are often used solely as user adjustment “knobs”, they can do so much more. This article explores the inner workings, types, key specifications, and advanced applications of potentiometers – far beyond just dialing in a level.

What is a Potentiometer?

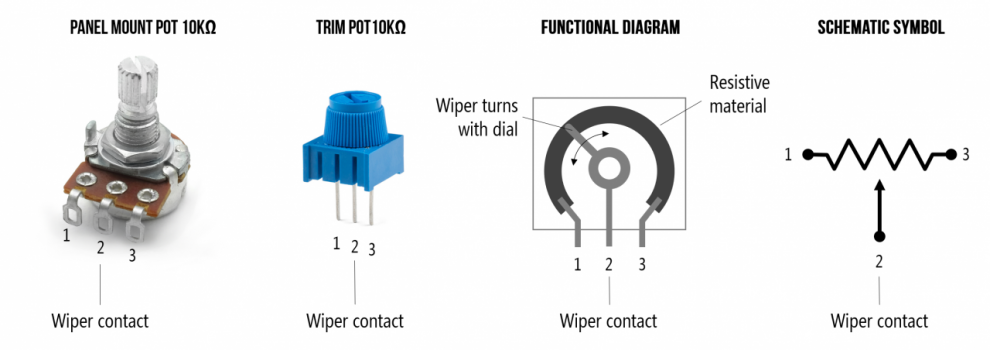

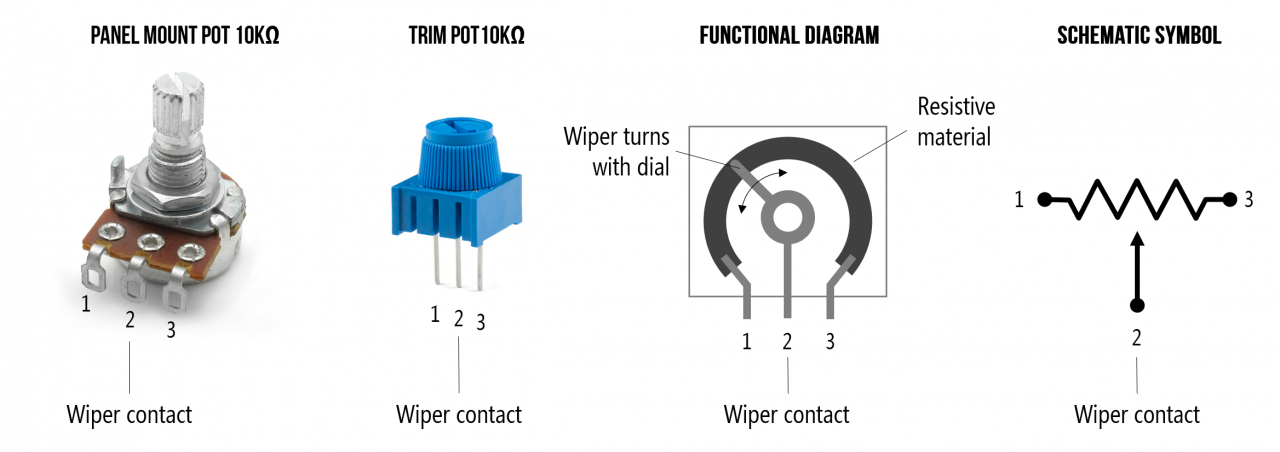

A potentiometer, often abbreviated pot, is a variable resistor that can alter circuit resistance in order to control voltage division. It consists of a resistive element, such as carbon film, and a wiper that slides along the element to tap off varying amounts of resistance. The wiper terminal connects to the center pin of a three-pin package. The two ends of the resistive element connect to the other two pins.

Rotating the shaft changes the wiper position, increasing or decreasing resistance between the center pin and each end pin. This adjustable resistance results in an adjustable voltage divider, providing a continuously variable analog output voltage that can span the device’s input voltage range.

Types of Potentiometers

While the fundamental operating principle is the same, potentiometers come in a variety of mechanical designs:

Single Turn

- Can rotate about 300 degrees

- Good for applications needing a limited adjustment range

Multi-Turn

- Can rotate many full turns

- Allows finer voltage adjustment over wide range

Slider

- Wiper slides linearly rather than rotates

- Often used in audio mixer and other slides

Trimmer

- Smaller potentiometer for infrequent calibration and tuning

- Adjustment done with a screwdriver rather than continuous

Motorized

- Wiper position actuated by a motor rather than manual

- Allows remote or automated analog control

Digital

- Wiper position set digitally by a microcontroller

- Provides analog programmability and control

This variety allows selecting the ideal mechanical interface for the intended application, from a simple user volume knob to a digitally programmable actuator.

Key Specifications

Some key parameters define the performance and operating constraints of a potentiometer:

Total Resistance

- Typically between 1kΩ and 1MΩ

- Sets maximum wiper output voltage

Tolerance

- Resistance accuracy, often ±10% or ±20%

- Affects output voltage precision

Power Rating

- Maximum wattage the pot can dissipate as heat

- Depends on resistor material and size

Taper

- The output to rotation relationship

- Linear or various non-linear tapers

Life Cycle

- Times pot can be rotated over lifetime

- 100k cycles typical for rotary types

Operating Temperature

- Range of ambient temperatures for reliable operation

Considering these specifications allows matching the potentiometer to the required electrical and environmental characteristics.

Potentiometer Applications

The humble potentiometer shows up in all kinds of circuits, thanks to its flexibility. Some common applications include:

Control Inputs

- Volume controls on audio equipment

- Tone adjustment on radios and guitar amplifiers

- Brightness knobs on lamps and displays

- Speed controls on motors and turntables

Sensing

- Position sensors by attaching a pot to moving parts

- Light sensors when paired with a photocell or LDR

- Gas pedal position sensors in vehicles

Instrumentation

- Voltmeters and other analog meter movements

- Adjustable gain on oscilloscopes

- Trim offset and scaling on op-amps

Timing Circuits

- Establishing RC time constants with capacitors

- Timing pots allow adjusting oscillator frequencies

- Can calibrate the duty cycle on pulse width modulation

Voltage Division

- Adjusting voltages and signal levels, e.g. a 5V to 3.3V level converter

- Biasing transistors and setting amplifier gain

- Partial voltage adjustments for testing circuits

And many more uses limited only by the imagination. Potentiometers provide continuously variable analog control to customize a vast array of electrical parameters.

Advanced Circuits and Techniques

While turning a dial is the most familiar use, there are more advanced circuit design techniques that exploit potentiometers in clever ways:

Summing Amplifier

Two or more potentiometers independently input into an op-amp summing amplifier. Allows mixing multiple analog signals like an audio mixer.

Buffered Output

An op-amp voltage follower buffer isolates the potentiometer from the following circuit, preventing loading effects on the wiper.

Constant Current Control

A pot in series with a power transistor can adjust current through a load for linear brightness control of lamps.

Pulse Width Modulation

Using a pot as part of an RC timing circuit driving a PWM generator allows variable duty cycle square waves.

Pseudo-Log Output

A fixed value resistor added from wiper to ground converts the output to a log-style response. Useful for audio controls.

Digital Control

Replacing the mechanical wiper with a digitally controlled multiplexer or R-2R ladder provides software-defined control.

These methods help tailor a potentiometer to specialized applications that demand capabilities beyond just simple passive voltage division.

Selecting the Right Potentiometer

With the wide variety available, here are some tips for selecting an optimal potentiometer:

-

Determine the needed total resistance and tolerance to meet voltage/current requirements.

-

Check the power rating – 1/4 watt pots are common but higher wattage may be needed.

-

Linear or audio taper? Audio logs the output for nicer volume control response.

-

Pick the right mechanical configuration – single vs multi-turn, slide vs rotary.

-

How many rotations or lifecycles will the pot undergo? Pick a sturdy model rated for heavy use if needed.

-

Consider the temperature range the potentiometer will operate in.

By evaluating these factors, you can choose the right potentiometer for the job that provides the desired electrical behavior in a suitable physical package.

Conclusion

While on the surface it seems like a simple three-terminal component, the potentiometer is a remarkably versatile tool for controlling analog voltages. It acts as a variable voltage divider, its output controlled by the position of the wiper. Rotary pots provide the familiar dial controls on electronics equipment, allowing adjustable control of signals and levels. The wide array of types, electrical specs, and creative circuit configurations enable potentiometers to adapt to an enormous variety of applications. They will continue to be ubiquitous across circuits ranging from consumer devices, to scientific instruments, to industrial equipment as an essential means of dialing in analog levels.